Creating story arcs with three-unit brackets

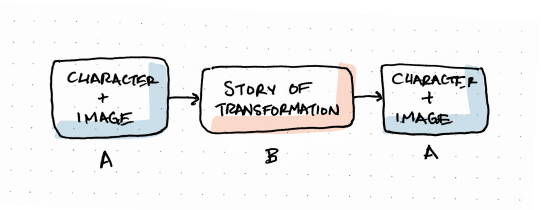

Summary: Bracketing is a three-unit story structure following an A - B - A form. It’s often used to illustrate transformation by returning to a familiar image, motif, setting, or situation where something has changed because of the intervening story.

In a couple of previous notes, We looked at two-unit story structures like simple comparison and contrast and Ira Glass’ anecdote and reflection. In this note, we’ll move on to a three-unit structure, which I call (for lack of a better term) bracketing.

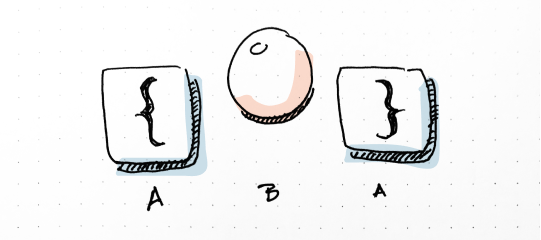

Bracketing is a basic storytelling structure in which the first and third elements, often a repetition of some sort, sandwich the second element between them. It follows the form: A - B - A.

If you’ve been through US high school English classes, you might recognize this as similar to chiasmus. True chiasmus is a mirrored pattern of four or more beats (A - B - B' - A'), so technically, bracketing isn’t chiasmus. Instead, you can think of bracketing as the fundamental form and all chiastic structures as more complex expressions built atop that foundation.

Many of us are familiar with bracketing as a line-level, poetic or rhetorical device. But, bracketing applies in broader contexts as well. Good storytellers can use elements of bracketing on the structural level to imbue their stories with added meaning.

In ancient literature, bracketing was commonly used to draw special attention or emphasis to the element in the middle. (See, for example, inclusio.)

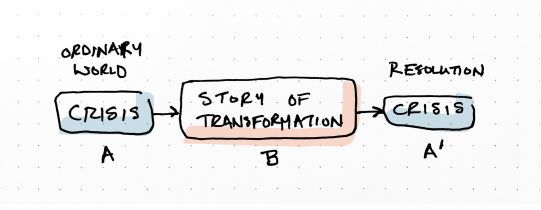

In modern story, bracketing can perform a similar function, often on the thematic level. For example, by showing a character’s differing responses to a similar situation repeated in the story’s opening and closing (represented by A and A' in the bracketing structure), a storyteller highlights the change caused by the story’s events (represented by B).

“If faced with [a] similar crisis . . . what your character chooses at the beginning hook of your story and what your character chooses at the end of the story should be opposite choices.”

— Shawn Coyne (Coyne, Page 185)

Brackets can place focus on plot in addition to character. Story theorists Robert McKee and Syd Field both explore, for example, how the inciting incident and story climax together establish a story’s dramatic question. (McKee, Page 202) (Field, Page 104) Author and story theorist K. M. Weiland agrees: “think of the Inciting Event as a question that the Climactic Moment must answer.” (“The crucial link”) (Emphasis mine.)

If we broaden our definition a little, we can even include things like callbacks as expressions of bracketing as well. In a callback, a phrase or motif is repeated, but the meaning has changed due to contextual changes in the story between.

How bracketing works

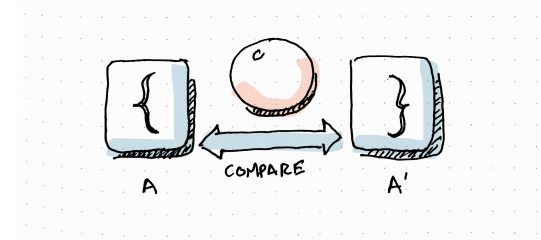

Bracketing works by exploiting comparison.

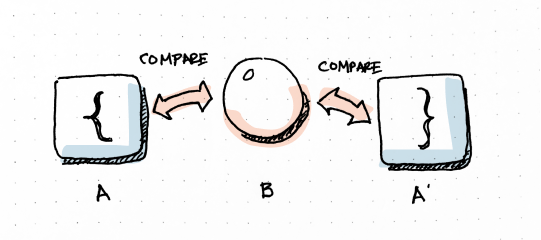

There are two sets of relationship comparisons in a bracketing arrangement. The first is the comparison between the bracketing elements themselves. What are the ways in which A is similar to A'?

The second is the comparison between the bracketing elements and the contents in the middle. In what ways are both A and A' different from B?

In more complex forms, there can also be important contrasts between the bracketing elements. A is different from A' because of what happened in B.

How to create bracketing

In order to create effective bracketing, storytellers must influence the relevant sets of comparisons.

That means, first and foremost, clearly communicating some kind of resonance between the two bracketing elements.

In the most basic form, storytellers can make the two elements exactly identical. Callbacks, for example, often involve a phrase or motif repeated word-for-word to establish the link.

In more complex forms, storytellers can play with the similarities and contrasts. Similarities draw the story units together and establish the relationship, while contrasts layer in additional meaning. The range of available tools for creating similarities and contrasts is almost as broad as storytelling itself, including things like imagery, setting, dialogue, plot situations, character actions, even the sequence and structure of events.

In Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film, Jurassic Park, for example the opening and closing scenes of Dr. Grant’s story thematically bracket his character arc. When he is introduced, Dr. Grant is shown digging up fossilized proto-birds, petrified in the solid rock (image), and he expresses dislike for children (character). At the end of his arc, we see him riding away from the doomed island on a helicopter, watching modern birds fly over fluid and ever-changing waters (image), a child at each side (character).

Together, these moments form tight, 1:1 contrasts with each other, establishing a set of brackets that underscore what happened between them, his character transformation.

Bracketing at multiple resolutions

Dr. Grant’s opening and closing images in Jurassic Park illustrate how the technique can work across the length of an entire story, but bracketing can work on the act-, sequence-, and scene-level resolutions as well.

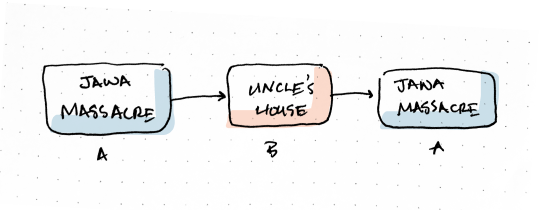

For example, in George Lucas’ 1977 film, Star Wars: A New Hope, Luke’s Crossing the Threshold sequence involves a brief bracket around place.

Immediately before the bracket, Luke has declined Obi-Wan’s invitation to go to Alderaan. The bracket begins as Luke and Obi-Wan arrive at the setting of a massacre. The Empire has slaughtered of a band of trading Jawas. Horrified, Luke recognizes these as the very same Jawas who sold droids to his family. He fears that the Empire will attack his family next. Luke rushes home, only to discover that the Empire has gotten there first. His uncle and aunt are dead, and his home has been destroyed. Luke returns to the scene of the Jawa massacre and declares that he will join Obi-Wan on the journey to Alderaan.

In this case, the most obvious bracketing comes from location. In both of the bracketing scenes, Luke and Obi-Wan are at the site of the attack on the Jawas. In the middle, Luke goes to his home and discovers that the Empire has killed his family.

If we go back one scene and include the final moments at Obi-Wan’s home, we can also discover a larger, slightly more complex, true chiastic structure. This one has to do with the decisions and revelation in the sequence.

At Obi-Wan’s home, Luke declines the Call to Adventure (decision). Then, Luke and Obi-Wan discover the attack on the Jawas (revelation). Luke goes home and discovers the attack on his family (revelation). Luke returns and tells Obi-Wan he wants to go with him (decision). This sequence creates a chiastic decision - revelation - revelation - decision structure, where the two revelations in the middle move Luke from denying to accepting the Call to Adventure.

Conclusion

Bracketing is a three-unit story structure that follows the form A - B - A. It’s often used in storytelling to illustrate transformation by returning to a familiar image, motif, setting, or situation where something has changed during the intervening story unit.

I hope it’s a helpful tool for you as you go and tell great stories.

Rate this note

Read this next

Creating meaning with two consecutive story units

Human brains can't help but look for patterns, even when nothing's there. Storytellers can leverage this tendency, juxtaposing images in order to create rich and layered meaning.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.