Beginning, middle, and end part 5: Character stories part 1

Summary: The key change in a character story is about worldview and beliefs. The beginning establishes the protagonist’s ‘lie,’ and the progress and disaster phases show how that lie is challenged.

“The Lie Your Character Believes is the foundation for his character arc. This is what’s wrong in his world. Once you know what’s wrong, you then get to set about figuring out how to make it right.”

— K. M. Weiland (Weiland, Page 15)

Character stories revolve around the choices of the protagonist. They’re explorations of identity. Who is this person, and why does she do what she does? Most importantly, how does she change (or why does she not change)? (Kowal) Strong character stories are generally the most emotionally moving of the story types.

- The key change in a character story is about the underlying beliefs that drive the protagonist’s behavior and view of herself and the world. (Weiland, Pages 13-16)

- The emotional fulfillment audiences derive from character stories is catharsis, often from the reaffirmation of their deeply-held values.

- The key turning points in character stories are the protagonist’s decisions.

Recap

This note is a part of a series.

- Aristotle misinterpreted

- In search of a useful framework

- Story types

- Idea stories

- Character stories part 1

- Character stories part 2

- Event stories

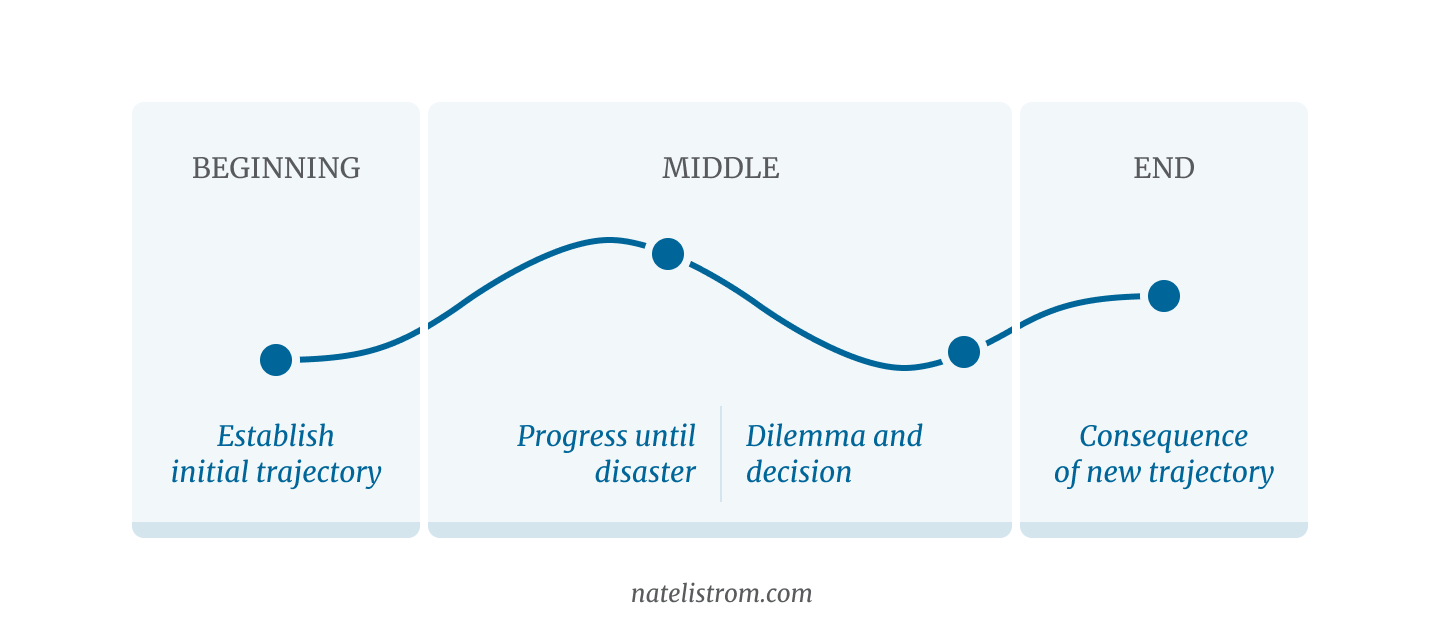

As a reminder, we’re trying to develop a useful structural framework based on Aristotle’s “beginning, middle, and end.” Aristotle’s definitions give us clarity for the beginning and end, and we’re using Dwight Swain’s scene-sequel format to fill in the middle.

Here’s what that looks like:

| Beginning |

|

|---|---|

| Middle |

|

| End |

|

The question is, does this theory fit character stories?

In this note, we’ll attempt the first part of an answer, covering the beginning and the middle up to the disaster. In the note that follows, we’ll pick up at the dilemma and go through to the end.

Beginning: Revealing a need

Most character stories begin with two key components:

- A “before image” with the protagonist living in stability in her ordinary, pre-change life. (Snyder, Page 72)

- A moment when that stability is challenged, setting her on a path toward confrontation with change. (Weiland, Pages 47-49)

Before image: establishing the lie

The before image establishes who the protagonist is and what about her needs to change to achieve a fulfilling life. (Vogler, Pages 104-109) (Weiland, Page 36)

It will later form a comparison with the “after image” at the story’s ending. Together, they’ll demonstrate what changed during the story. (Snyder, Page 72)

Character stories are all about need. (Truby, Pages 40-44) The protagonist may want some external goal, but there’s something deeper going on. What she really needs is to change on a heart level. Her need has to do with her beliefs about herself and the way the world works and how to live in it. This can be expressed as a “lie” that she believes. (Weiland, Pages 13-16)

The protagonist’s choices and actions during the opening image are an external manifestation of the lie. It’s helpful if the negative consequences of her belief are on display, though she won’t yet understand them (and may not even acknowledge them). (Weiland, Page 14) (Truby, Page 276)

To reach a point of wholeness, the lie upon which the protagonist has based her worldview must be corrected.

Pride and Prejudice

In Jane Austen’s 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice we see a before image of Elizabeth Bennett and her family. She is the second of five daughters, clever and assertive.

Because of their circumstances, Elizabeth and her sisters are under pressure to marry for financial stability, but Elizabeth wants her marriage to be marked by love and, above all, mutual respect.

Her cleverness can get her into trouble. She judges others too quickly — without taking the time to understand them deeply. This hints at her lie: that she can trust her cleverness alone to judge people’s character.

Jurassic Park

In Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film Jurassic Park, we meet Dr. Grant, a paleontologist. He’s leading a dig to unearth fossilized velociraptors. He has an uneasy relationship with new technology, and he can’t stand children. When a kid on the dig site makes fun of his beloved dinosaurs, Dr. Grant antagonizes the child with a fossilized raptor claw.

We don’t know it yet, but each of these things is a symbol for how Dr. Grant is stuck. He’s afraid of the uncertainty of the future, metaphorically just as much buried in the immovable past as the dinosaurs he cares about.

We also learn that Dr. Grant has a minority opinion theory that the velociraptors evolved into modern-day birds. They learned to fly, and the story will show us that, in a sense, Dr. Grant must do the same.

Moment of destabilization

The trajectory itself is introduced by the call to adventure and the protagonist’s subsequent decision to “cross the threshold.” (Vogler, Page 151) (Weiland, Page 47) Something happens that threatens her safety in her lie, and she must respond.

Up until this point, the protagonist has been broken but happily unaware. Now, she’s forced onto a path that will eventually lead her to a confrontation with a deep, uncomfortable self-understanding.

This is the first moment of engagement, what in Aristotle’s terms might be called the “beginning of causality.”

Pride and Prejudice

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth’s quick judgment comes into focus when wealthy gentleman Fitzwilliam Darcy declines to dance with her at the Meryton ball.

It’s a minor social faux pas, not a significant action beat like we’d expect from, say, an event story. But it has its significance. It sets Elizabeth on a journey. How will she deal with Darcy and his apparent arrogance? (Spoiler: she judges him.)

In time, she will be forced to deconstruct her judgment of Darcy and question her idea of what makes an ideal suitor.

Jurassic Park

It’s challenging to identify the call to adventure of the character story in Jurassic Park. The main call to adventure is when park owner John Hammond visits Dr. Grant’s and Dr. Sattler’s dig and offers to fund their work in exchange for their expert review of his park. But that call is tied to the event story, not the character story.

If I had to place it, I’d put Dr. Grant’s call to adventure at the moment when, riding into the park in the back of a Jeep, he sees the Brachiosaurus for the first time. This is his introduction to the fact that the world has changed. He’s now on a collision course with the uncertain future he’s tried so hard to avoid.

Middle part 1: progress and disaster

When the protagonist is confronted with the main challenge of the story, her first response is usually to try to protect and maintain her current, flawed worldview. Change has a cost. It takes energy, and we’re hard-wired to conserve energy.

The protagonist can’t avoid her new situation, but she’ll try to navigate it in a way that preserves her old self. The middle of the story plays out the drama of whether or not she’ll succeed.

As the protagonist pursues her plan, she meets growing resistance until something happens that makes further progress impossible. This forces her to search for, find, and commit to a new trajectory. We can think of that as the following sequence: progress, disaster, dilemma, decision. In this note, we’ll cover the first two.

Progress

During the progress phase of a character story, the protagonist navigates her new situation basing her actions on her old, preexisting beliefs.

At first things may seem to go well. With anything new, there’s a period of initial exploration. You could think of this as a “honeymoon” phase. The novelty of the new situation makes it interesting. True, there may be some shyness and uncertainty, but the emotional note is generally positive.

However, as things progress, it becomes increasingly difficult for the protagonist to continue lying to herself. The world confronts her with greater and greater challenges, forcing her to expend more and more effort to preserve her mistaken beliefs.

Pride and Prejudice

In Pride and Prejudice, this phase sees Elizabeth Bennet navigating interactions with three potential suitors.

-

Darcy

Elizabeth’s sister, Jane, falls ill. Elizabeth goes to care for her, which forces her into proximity with Mr. Darcy. They spar, continuing to misunderstand one another. Elizabeth’s dislike for him deepens. -

Wickham

Elizabeth meets a charming young army officer named Wickham, who appears to be clever and winsome. Her quick, shallow judgment leads her to accept his self-presentation without question. But although Wickham seems to confide in Elizabeth, he pursues other women for their wealth. -

Collins

A clergyman named Collins proposes to Elizabeth and she (rightly) rejects him. Although his means and position in society are acceptable for marriage, he’s a fool, a sycophant, a buffoon. Elizabeth could never respect him.

Elizabeth’s misjudgments of Darcy and Wickham make her ideal unreachable. With each failed match, the prospect of happy marriage with love and respect seems father and father away.

Jurassic Park

In Jurassic Park, Dr. Grant and the other experts marvel at the wonders of the park. But then they begin to explore the implications more seriously. They speculate about negative consequences.

Park owner John Hammond’s grandchildren arrive. They’re a test audience, representing the park’s target market. Dr. Grant tries politely to avoid them. He ends up spending time with Dr. Malcolm instead, a man who wholeheartedly embraces the chaotic uncertainty of the future. Humorously, Dr. Malcolm’s casual relationship with uncertainty makes Dr. Grant uncomfortable.

Each beat pushes Dr. Grant farther and father out of balance. He’s slowly but surely being driven to a crisis point.

Disaster

If the progress phase is like movements on a chessboard, the disaster is checkmate. In the story, something happens that makes it impossible for the protagonist to continue in her chosen trajectory.

In a character story, the disaster is most meaningful if somehow related to the protagonist’s broken worldview. She needs to change. And because the plan she initially selected was bent on preserving her old self, it was doomed to fail.

Pride and Prejudice

In Pride and Prejudice, there are two “tentpole” disasters. The second of them comes at what screenwriting consultant Blake Snyder might call the “all is lost moment.” (Snyder, Pages 86-87)

Leading up to this moment, Elizabeth has come to see a completely different side of Mr. Darcy. She’s been with him “in his element” and come to realize that perhaps there’s more to him than she at first thought. She softens. We wonder if perhaps the two might fall in love after all.

But then Elizabeth’s sister, Lydia, elopes with Mr. Wickham. This impropriety will bring Elizabeth’s family into disrepute. Darcy appears at the very moment Elizabeth learns of the event. In her distress, she admits to him what has happened. Darcy, for whom social respect is of importance, is grave. He is polite and caring but departs quickly, leaving Elizabeth to assume that he wants never to see her again.

This “all is lost” brings Elizabeth’s mistaken judgments of both Darcy and Wickham into focus. She originally thought well of Wickham, who turns out to be a scoundrel. She thought poorly of Darcy, who now might possibly turn out to be a true gentleman.

Her quick wit and sharp judgment, on which she has relied her whole life, have failed her in both cases.

Jurassic Park

Dr. Grant’s character story disaster proceeds as a direct result of the midpoint disaster in the event story.

The Tyrannosaurus rex escapes its paddock. Dr. Grant summons his scientific knowledge — and an admirable level of selfless bravery — to rescue the kids from the colossal predator.

But this saddles Dr. Grant with exactly the kind of situation he’s been trying all along to avoid: He’s now stuck, responsible for guiding two children through the wilds of a park overrun by dinosaurs.

He cannot continue his policy of stubbornly avoiding uncertainty. He’s forced to confront chaos head on.

To be continued . . .

In the next note, we’ll pick up with the dilemma and decision that lead to the climax of a character story.

Until then: Onward . . .

Rate this note

Read this next

Beginning, middle, and end part 6: Character stories part 2

The key change in a character story is about worldview and beliefs. The dilemma and decision show how the protagonist grapples with change, and the ending demonstrates that her change was genuine.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.