Use one scene-sequel cycle each act

Summary: In a Western Character-event story, the scene-sequel cycle repeats three times on the act level. Using ‘Star Wars: A New Hope’ as an example, we examine how that works and how you can use it for your stories.

Luke Skywalker just can’t catch a break. All he wants to do is go to Toshi Station to pick up some power converters with his friends. But his uncle needs help on the farm. They buy some droids. Luke (being free, available labor) gets tasked with cleaning them up. Farm life. Le sigh.

Then, while doing the job, Luke discovers part of a recorded message of a pretty young lady. Naturally, he wants to see the whole thing. But the dumb droid flatly refuses to play the message unless Luke removes its restraining bolt. Usually, that would be a bad idea — the droid could run away — but Luke lives way out in the middle of nowhereville with miles of sanded wasteland all around, so where could the droid possibly run to? Besides, the girl looks so pretty . . .

So Luke removes the restraining bolt. And, whaddayaknow, at its first opportunity, the droid runs away. A

This sends Luke on a wild goose chase to run down the droid before catching his uncle’s ire. Long story short, he intercepts the droid, runs into some trouble, gets out of it thanks to a crazy old space wizard, gets invited to go on a quest with said wizard (and declines), and then finally makes it home . . . only to discover that his life had been completely upended in the mean time. The Empire’s troops have burned out his home and killed his uncle and aunt.

What to do now? What would any rational person do in such circumstances?

Join the space wizard on an epic quest of course!

Okay, dialing down the sarcasm for a moment . . .

Buried under all the Saturday serial melodrama, we’ve just witnessed a subtle and deft application of storytelling technique. Lucas deploys a perfect and powerful example of what author Dwight Swain called “scene and sequel.”

What are scenes and sequels?

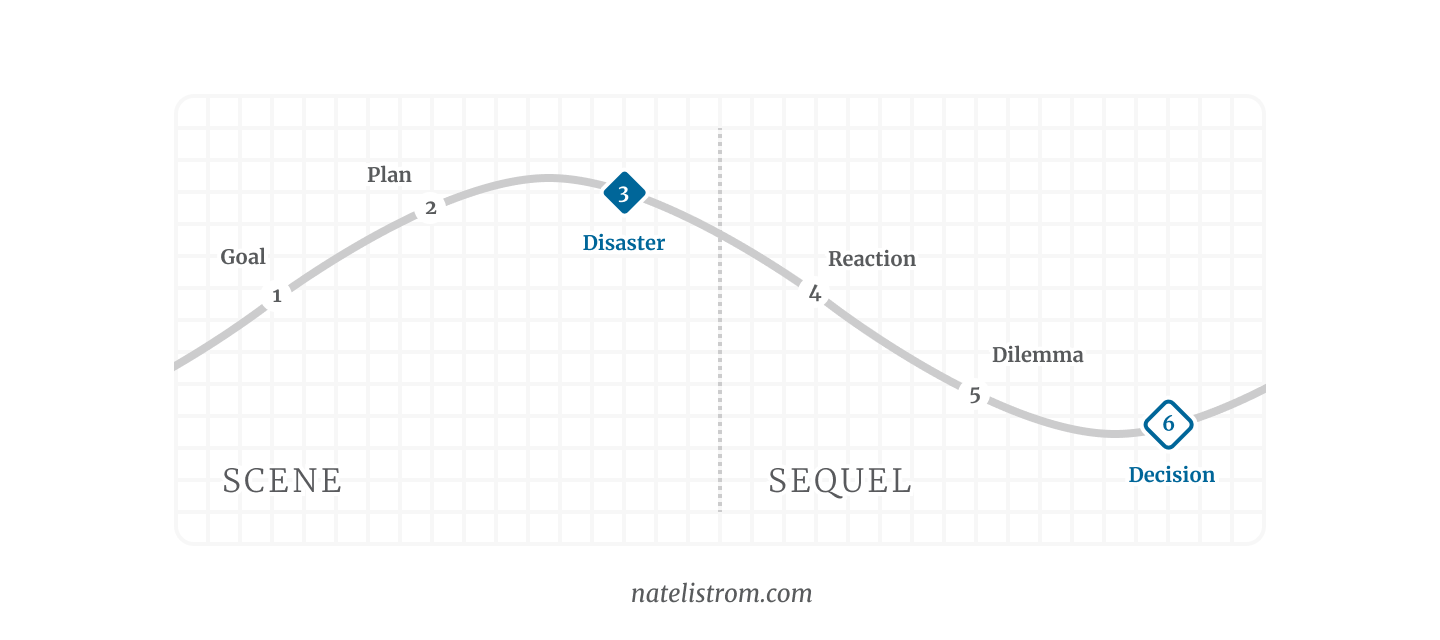

Scenes are an action-based progression of what Swain calls goal, conflict, and disaster. (Swain, Page 85)

- Your protagonist has a desire she is pursuing (goal). Some form of opposition threatens her ability to obtain her goal (conflict). Then, when the conflict reaches its peak, there’s a crescendo: a “logical, yet unanticipated development” ends her plans in disaster. (Swain, Page 89)

- Luke wants to goof off with his teenaged friends, but a mountain of obstacles gets in the way. This escalates to the discovery that his home has been destroyed.

Sequels are the character-based response, a progression of reaction, dilemma, and decision. (Swain, Page 100)

- Reeling from the shock of the disaster, your protagonist must process what has happened and take stock (reaction). What will she do now that her plan is in shambles? The answer must never be easy. Your protagonist faces a dilemma, what Story Grid founder Shawn Coyne calls a crisis of “best bad choice” or “irreconcilable goods.” (Coyne, Pages 177-178) In Swain’s parlance, it’s a “choice between equally unsatisfactory alternatives.” (Swain, Page 101) Once she’s grappled with the implications of her options, she makes a choice (decision).

- Luke goes back to the space wizard, and decides to join him on the quest.

The decision at the end of a sequel naturally leads to a new goal (or a new plan to achieve the existing goal), and the whole cycle repeats.

When I think of scene-sequel format, I substitute “plan” in place of “conflict.” It’s really the same thing, just from a different perspective. I find it’s easier to generate meaningful conflicts if there’s an identifiable plan that the protagonist actively pursues. This gives the antagonistic force something concrete to attack. Without this target, I risk creating misaligned conflicts that distract from the story’s central drive.

Thus, the full progression becomes goal, plan, disaster, reaction, dilemma, decision.

Swain applied his insight on the level of individual story scenes, but here, we’re applying scene-sequel format to larger structural units. This is where the magic happens.

Applying scenes-sequel format to the map

As a reminder, this note is the second in a series exploring how to apply story structure frameworks. Story frameworks are like maps. They help you know where you are and where you’re going, but they’re not the terrain itself.

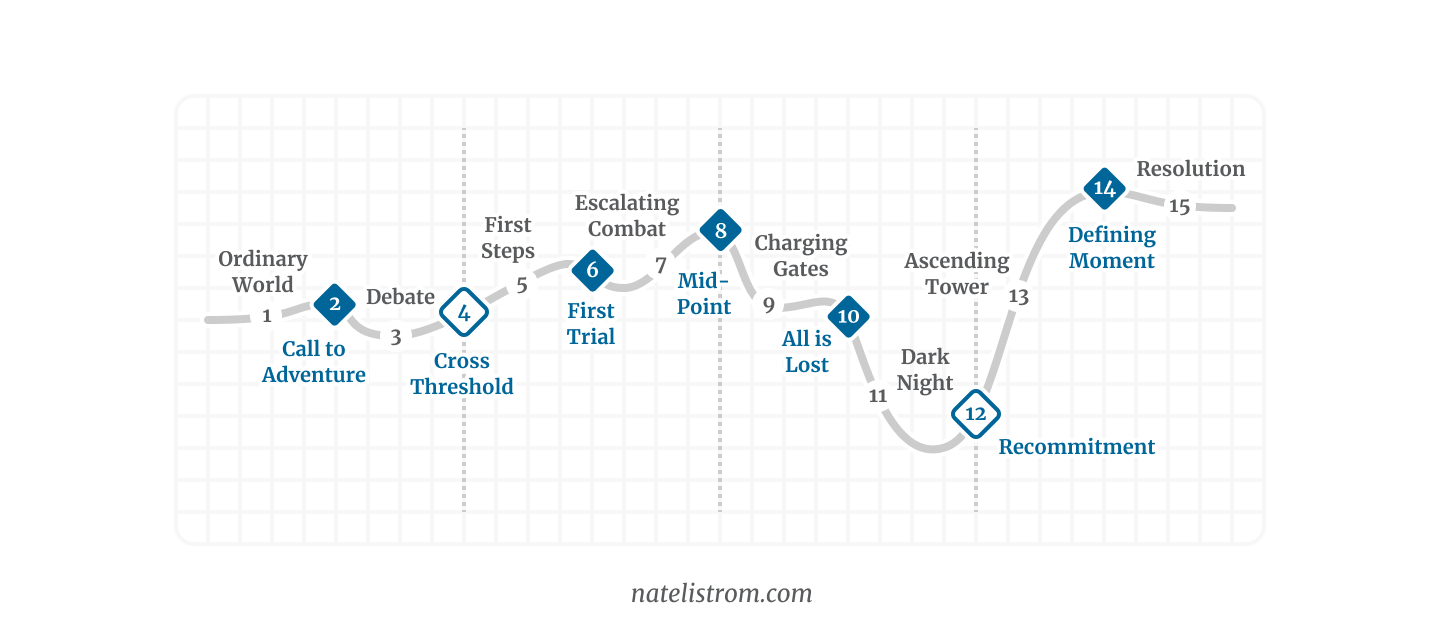

In a previous note, I laid out the map that I’ve found to be the most useful to me, personally. It’s cobbled together from a number of other story frameworks. Here’s a summary.

If we look back at our act structure, we can see the scene-sequel pattern play out exactly two and a half times across the story map.

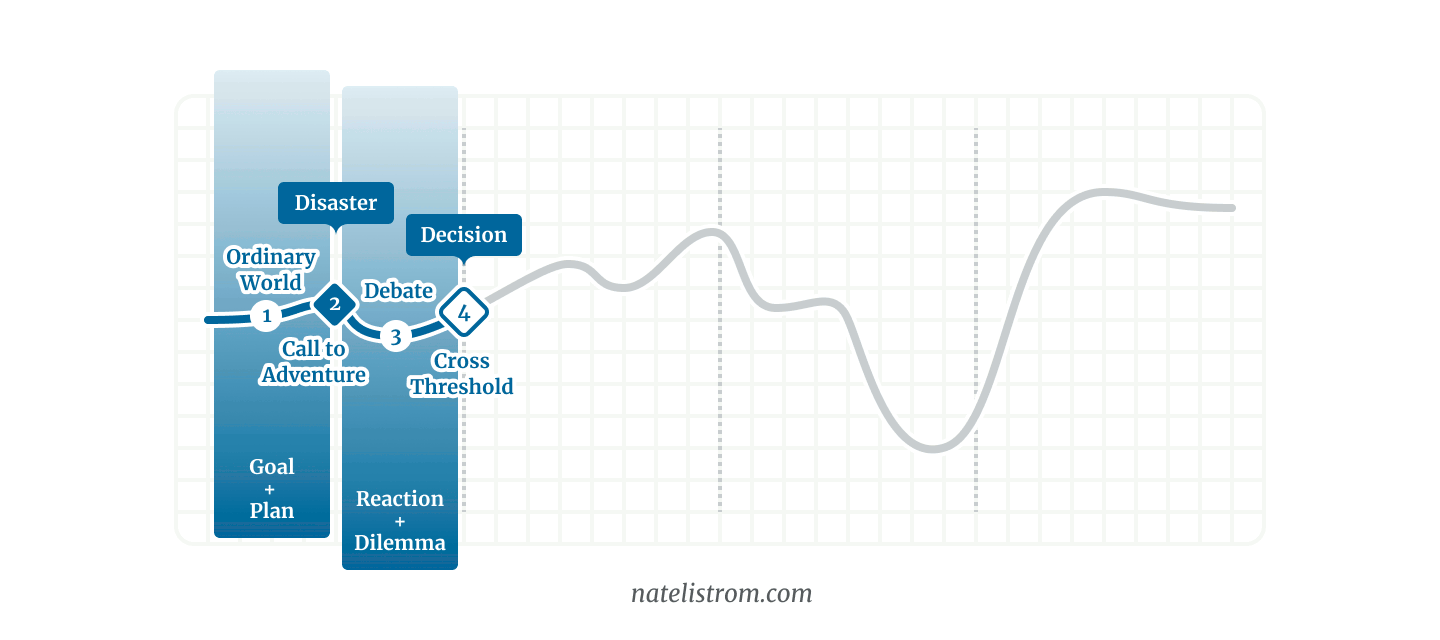

Act I: the first cycle

The purpose of the first act cycle is to transition the protagonist from being ignorant of the main story goal to making a decision to actively pursue it.

| Beat | Example from Star Wars |

|---|---|

| Ordinary World (Goal and Plan): Your protagonist pursues a preexisting goal and plan. (This is a goal and plan that comes before the main story, but it’s a goal and plan nevertheless.) | Luke starts off as a naive farm kid who dreams of big adventures. |

| Call to Adventure (Disaster): Something happens to your protagonist that disrupts her plan. | Obi-Wan Kenobi (the aforementioned space wizard) introduces Luke to his heritage and invites him to go to Alderaan and learn the ways of the Force. |

| Debate (Reaction and Dilemma): Your protagonist responds to the disruption caused by the Call to Adventure and considers her choice of what to do next. | Confronted with a real, actual adventure (read: change), Luke begs off. It’s too different, and he wants to return to his normal life. |

| Decision to Cross the Threshold (Decision): Having evaluated the pros and cons of her options, your protagonist chooses a way forward and accepts the main story goal. | Luke experiences the Empire’s cruelty first-hand. Stormtroopers kill his uncle and aunt and destroy his home. He cannot return to his normal life. He decides to join Obi-Wan on the quest. |

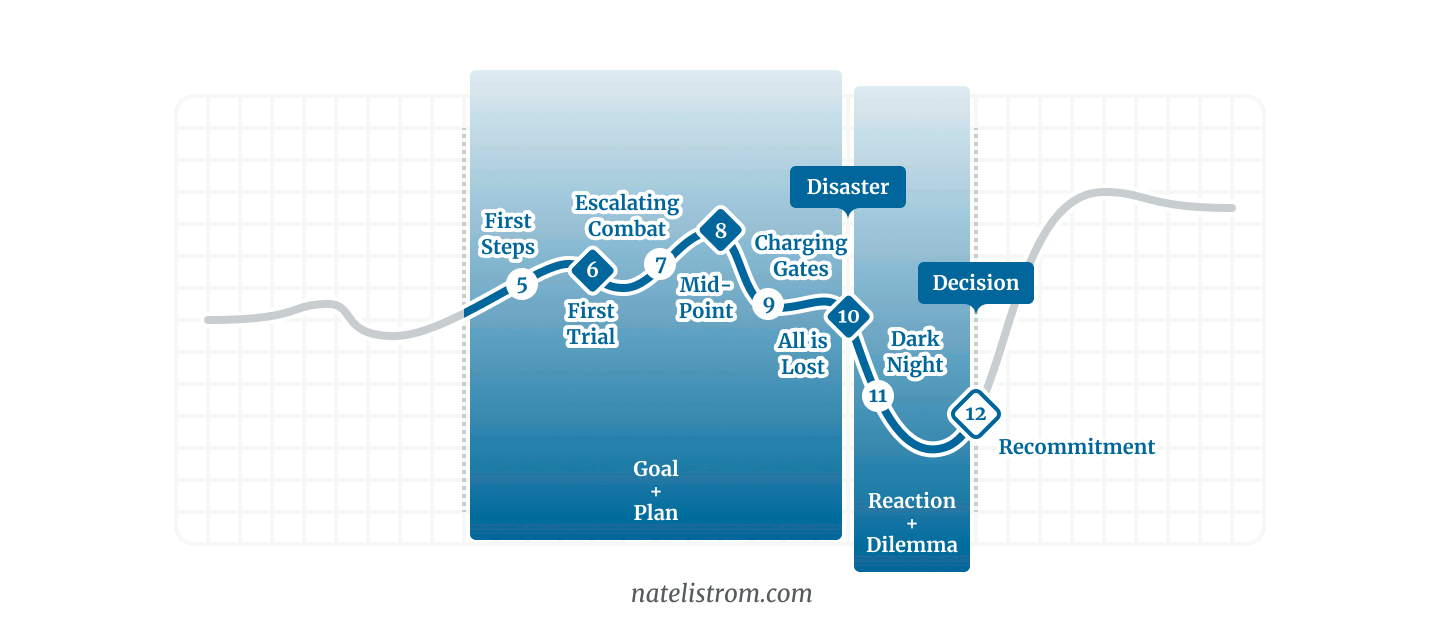

Act II: the second cycle

The second scene-sequel cycle spans the entire arc of Act IIA and Act IIB. In a Western Character-Event story, its purpose is to transition the protagonist from being ignorant of the lie she believes to a decision to reject it and accept the truth.

| Beat | Example from Star Wars |

|---|---|

| First Steps in a New World, First Trial, Escalating Combat, Midpoint, Charging the Gates (Goal and Plan): Your protagonist explores her new situation and pursues her plan and goal in the face of increasing resistance. Instead of encountering one main disaster, as in Act II, she encounters an escalating series of them. I think of this section of the story sort of like an accordion — it can expand or contract depending on dramatic need. The key is that the function is the same. | Luke follows Obi-Wan to a seedy port town where they hire a pilot to smuggle them off planet. They narrowly escape an Imperial blockade only to arrive at their destination and discover that the Empire has already completely destroyed it. Worse yet, the Empire captures them and attempts to imprison them aboard the Death Star, a huge battle station. They escape, but the Empire pursues them to the Rebel base. The Rebels attack the Death Star, and things seem to go well at first. But then, the evil Darth Vader enters the fray, and the Rebels begin to suffer loss. |

| All is Lost (Disaster): Your protagonist encounters a final, culminating disaster. It caps the series of Act II conflicts and definitively upends her plan. | The Rebels’ attack falters as Vader systematically eliminates their fighters. Luke starts his attack run. Vader shoots down Luke’s squadmates, killing Luke’s childhood friend. Then Vader sets his sights on Luke. There is no way out. |

| Dark Night of the Soul (Reaction and Dilemma): Eventually realizing that the source of her failure is not external but internal, your protagonist must grapple with the dilemma of whether or not to change. (Mazin) | After watching friends die, with Darth Vader on his heels, Luke faces a choice: Will he embrace the Force? |

| Recommitment (Decision): Your protagonist chooses what to do. She accepts the truth. (Or, in a tragedy, she knowingly doubles-down on a lie.) (Weiland, Pages 148-149) | Luke switches off his targeting computer, signaling his willingness to trust the Force. |

Act III: the third, open-ended cycle

The purpose of the Act III scene-sequel cycle is to merge and complete the open threads created by the first two cycles.

- In the Act I cycle, the protagonist accepted the story goal.

- In the Act II cycle, she rejected her lie and accepted the truth.

- In the Act III cycle, she embodies the truth and obtains the goal.

| Beat | Example from Star Wars |

|---|---|

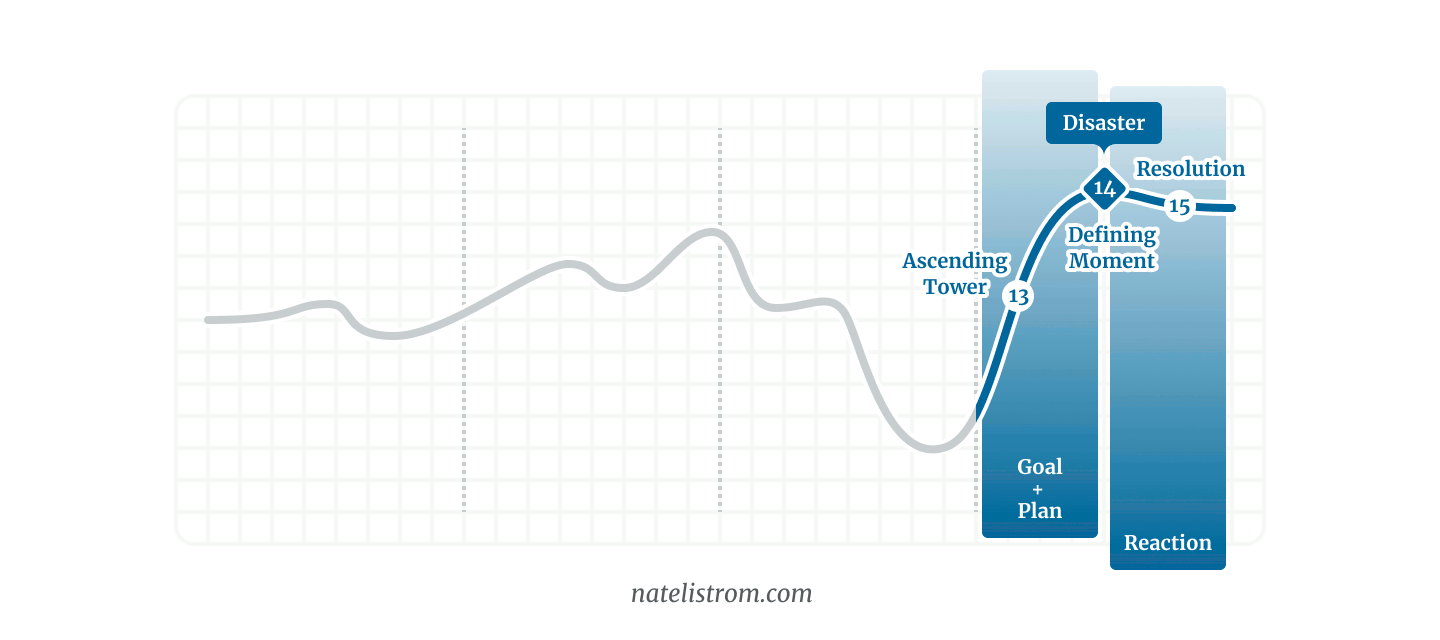

| Ascending the Tower (Goal and Plan): Newly equipped with the truth, your protagonist pursues a fresh plan to achieve the story goal. | Luke keeps after his target. Darth Vader shoots Artoo. Luke persists, but Vader is at his heels. Then, at the last minute, Han Solo swoops in with the sun at his back and guns blazing. Vader’s wingman flinches, clipping Vader’s fighter, which spins off into space. |

| Defining Moment (Disaster): Your protagonist embodies the truth of the theme through action. This is a sort of inverted disaster. Rather than ruining the plan, this turn fulfills it. Finally living in the truth, your protagonist obtains her goal. | Trusting the Force, Luke fires his proton torpedo. |

| Resolution (Reaction): Your protagonist lives in the new balance brought about by her actions in the defining moment. Because things are now settled, there is no dilemma and thus no need for a further decision. | Luke’s torpedo goes into the exhaust port and reaches the main reactor, causing a chain reaction that destroys the Death Star. Triumphant, Luke and his friends return to the rebel base. Artoo is repaired. The Rebels celebrate with an award ceremony at which Luke and his friends are honored. |

Applying scene-sequel format to your own work

The main way people think about applying scene-sequel format is on the level of individual scenes. And that’s a great way to build a story. It will help keep your story interesting, moment to moment, as your protagonist faces disasters, navigates dilemmas, and makes decisions.

But there’s another level. You can also use scenes and sequels as a tool to help you frame your protagonist’s overall journey.

Like Luke in Star Wars: A New Hope, your protagonist can:

- Live her ordinary life. (Act I goal and plan)

- Encounter an event that upends her stability. (Act I disaster)

- Deliberate about how to respond. (Act I reaction and dilemma)

- Accept a new goal. (Act I decision)

- Form a plan, and pursue it in the face of increasing resistance. (Act II goal and plan)

- Reach a breaking point at which she can no longer continue with her plan. (Act II disaster)

- Discover that what’s holding her back is not external but internal — a difficult change she needs to make. (Act II reaction and dilemma)

- Decide whether to change or not change. (Act II decision)

- Renew her pursuit of the story goal. (Act III goal and plan)

- Act on her commitment and achieve her goal. (Act III “inverted” disaster)

- Return to stability in a new balance. (Act III reaction)

Next up, we’ll look at how scenes and sequels help us identify and build key turning points in stories.

Until then . . . Onward!

Rate this note

Read this next

Applying scene sequel format to story structure

Author Dwight V. Swain's scene-sequel format applies on a broader level to entire act structures.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.