Turning points are disasters and decisions

Summary: A look at the 1998 romcom ‘You’ve Got Mail’ shows us that Dwight Swain’s scenes and sequels are an ideal tool for crafting compelling turning points.

Kathleen Kelly owns a tiny, boutique children’s bookstore called “Shop Around the Corner.” It’s a dear little store that her mother owned before her and has served generations of New Yorkers. Kelly loves Shop Around the Corner. For her, it’s more than just a bookstore; it’s her mother’s legacy. In a significant way, it’s Kelly’s identity.

But then, the big, bad, big box superstore Fox Books announces plans to open next door. The chain threatens to dominate the area, undercutting prices and overwhelming competition with a deeper catalog, broader inventory, and higher sales volume.

Suddenly, Kelly is in a fight for her store’s very existence.

She seeks counsel. On the advice of her Internet friend, she “goes to the mattresses.”

She decides to fight.

You’ve got turning points

I’ve just described the first two major turning points in the 1998 romantic comedy, “You’ve Got Mail,” written by Norah Ephron. When Fox Books shows up, threatening the Shop Around the Corner, that’s Kelly’s call to adventure. When she decides to fight back, it’s her decision to cross the threshold.

Here’s the question we’ll explore today: how do you and I create effective turning points? The skills to analyze and synthesize are different. It’s one thing to examine a well-written story. It’s another thing to sit down at the keyboard and actually wrestle through the development of your current work in progress.

To solve the riddle, we’ll need to find the right tools. A hammer’s great for driving in nails. It’s less useful for turning screws. So also, we want the right gear to build turning points with confidence.

Defining turning points

In his landmark work, Screenplay, author and screenwriter Syd Field describes turning points as “any incident, episode, or event that hooks into the action and spins it around in another direction.” (Field, Page 143) That’s a decent start, but it’s always felt a bit vague to me. How do you make the action “spin . . . in another direction”? What about stories that don’t turn on action?

Story Grid author Shawn Coyne gives us a bit more. To him, a turning point is “the moment when new information comes to the fore, and a character can’t help but react.” (Coyne, Page 168)

That’s more workable. A turning point is a revelation that demands a response. In fact, this definition is nearly sufficient. But while Coyne delivers great insight, with help, we can take this just a bit further.

Scenes and sequels help you place your turning points

If you’re familiar with my work, you’ll know that I’m a huge fan of author Dwight Swain’s scenes and sequels, which he explores in Techniques of the Selling Writer. Swain applies scenes and sequels on the level of individual scenes in his stories, but I think the pattern applies to sequence- and act-level structures as well.

Scenes and sequels are thus perfect for our needs. They provide a clear definition of both externally and internally motivated turning points. And, they give us a clear roadmap for where to place turning points and why. They tell us the what, but they also give us the tools for the how.

Here are our definitions:

-

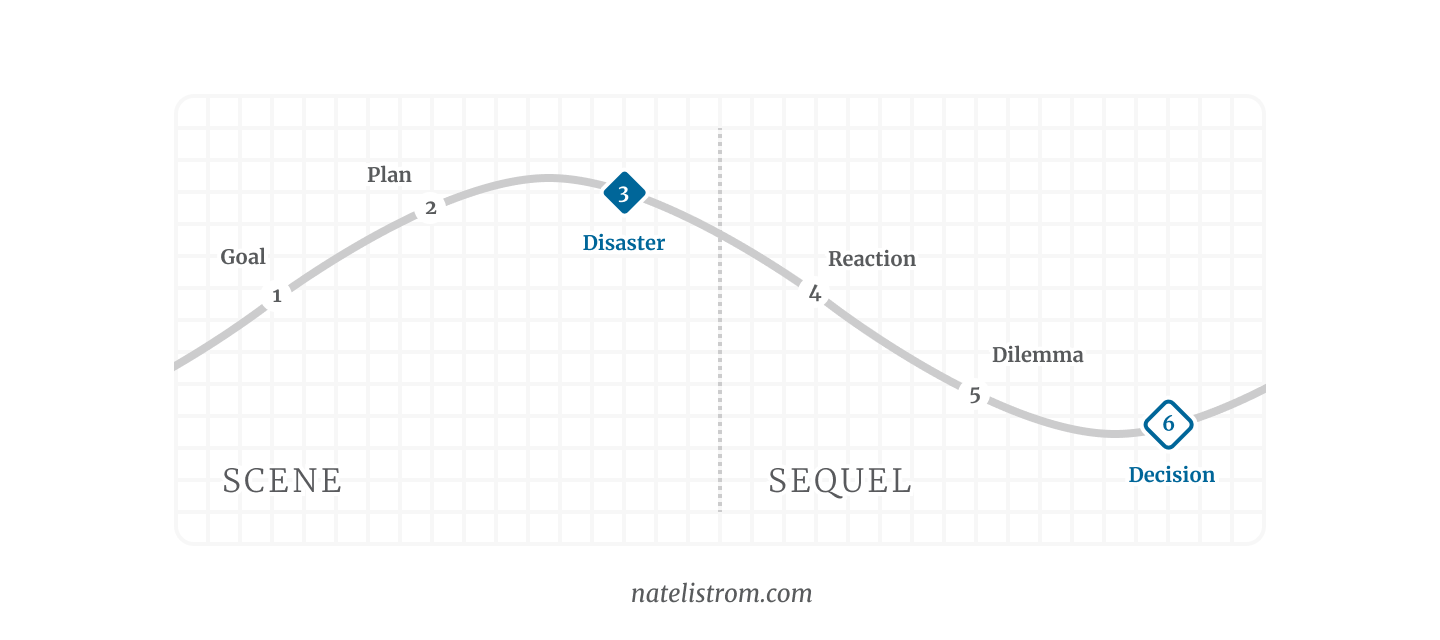

A scene involves a character who has a goal and pursues a plan to get her goal. She faces rising resistance to her plan until the scene ends with a disaster that makes it impossible for her to continue pursuing her goal in the way she planned. (Swain, Page 89)

Goal→Plan + Resistance→DisasterIn “You’ve Got Mail,” the story opens with Kathleen Kelly pursuing her ordinary life. Her goal is something like living up to her mother’s legacy, and her plan is to do that by faithfully running her shop. But then disaster strikes. Fox Books moves into the neighborhood, introducing an existential challenge to the Shop Around the Corner. Kelly cannot just bury her head in the sand and hope the problem goes away. She is forced to deal with it. Her plan (and thus the story’s direction) must change.

-

A sequel involves the character reacting — first emotionally and then logically — to the disaster. Reeling from the disruption in her plan, she takes stock, evaluates her options (what Swain call a “dilemma”), and then makes a decision. (Swain, Page 100)

Reaction→Dilemma→DecisionIn “You’ve Got Mail,” Kathleen Kelly’s reaction and dilemma center around a period of absorbing and processing the risk and then trying to decide what to do. It’s not a lot of screen time — sequel arcs often don’t need to be as long as scene arcs — but it’s there. Once she talks to her friend, she makes a decision: she won’t go down without a fight. This caps the sequel arc and establishes a new plan for the next section of the story.

Did you catch it? It’s subtle, but oh, so powerful.

Swain’s scenes and sequels have turning points built in.

-

The turning point in a scene is the disaster. Up until the disaster, the story proceeds in a set “direction” because the protagonist’s goal and plan are unchanged. But the disaster forces her to abandon her plan. That changes the direction.

-

The turning point in a sequel is the decision. When she makes a decision, the protagonist establishes a new plan. This sets up a new direction for the next section of the story.

How to use disasters and decisions in your story

“Okay, theory’s fine,” you may say, “but how do we use these tools, practically?” It’s a good question. I find Randy Ingermanson’s “Writing the Perfect Scene” to be an excellent resource. I encourage you to check it out. But I’ll give you a bit of my perspective here, too.

Write disasters that disrupt the plan

To me, disasters are the easiest to implement. To build good disasters, you just need to know what your protagonist’s concrete goal is and how she plans to get it. As long as the audience cares about whether or not she achieves that goal (that’s a topic for another day), they can’t help but care when your disaster threatens the goal.

The key to remember is this: the disaster must disrupt your protagonist’s plan in a way she cannot ignore. If there had been a fire at the Shop Around the Corner that burned up Kathleen Kelly’s inventory, she could raise funds from her community and rebuild. It would be terrible, yes, but it wouldn’t change her plan. Fox Books, on the other hand, is an ideal disaster because it forces her to change her plan.

If your disaster directly attacks your protagonist’s plan, it will always feel important and create narrative drive.

Write decisions that stay faithful to your protagonist’s motivations

In my experience, decisions can be a little bit harder. This is because there’s often a tension between what’s convenient for you as an author and what your characters are most likely to do.

Authors need to advance the plot. But realistically motivated, reasonable characters have all sorts of conflicting reactions and motivations. Those often get in the way. And compelling character decisions must be properly-motivated. It’s hard work building in that motivation.

Thankfully, that’s exactly what the reaction and dilemma phase of the sequel is all about. It’s where you “earn” the motivation for the decision that your protagonist makes.

So if you want your protagonist to decide to woo the billionaire, join the navy, or take down the Evil Empire, the reaction and dilemma phase is where you have them consider the alternatives like a reasonable person, try to find an easier way out, and slowly, grudgingly realize that pursuing that goal and plan really is the only viable option.

A good decision is a fantastic turning point because it feels both difficult and inevitable. Kathleen Kelly is “going to the mattresses.” She’s deciding to fight.

Next up, we’ll talk more about how turning points are moments and how those moments relate to the spans of story that connect them, but this enough for now.

Onward!

Rate this note

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.