Story is a material for the mind

Summary: Every material has unique advantages and disadvantages, which affect purpose, process, and experience. Thinking about story as a material gives you insight into how to improve your storytelling.

Purely for the joy of it, I took four semesters of ceramics in university. In that time, I learned quite a bit. I familiarized myself with how to hand-build and how to throw pots on the wheel. I made cylinders and bowls and vases and teapots and even some double-walled vessels. It took me a while, but by the end I’d learned how to pull handles that looked half-decent, something that’s notoriously difficult for beginners.

But across those two years of studying the craft, there was one task which I never even came close to mastering: trimming beautiful, well-crafted feet.

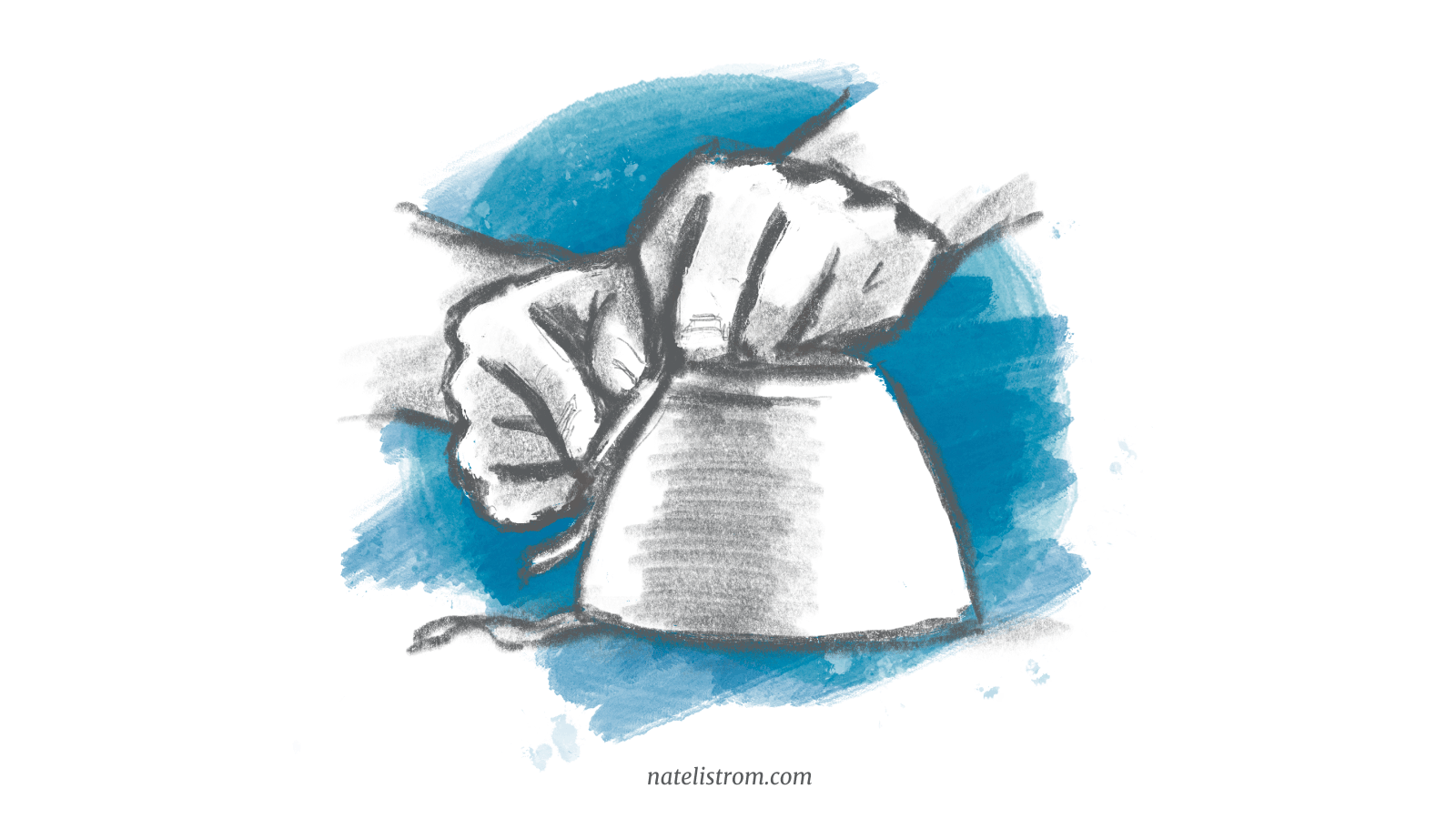

When you throw a pot on a wheel, you center a lump of clay on what’s called a “bat.” The bat is a flat disk that sits on top of the wheel and makes it easier to swap out pots quickly. Once you’ve made your vessel, you must remove it from the bat by cutting it away. You usually do this by running a metal wire underneath the vessel as close to the surface of the bat as possible.

The cut from the wire leaves the bottom of the pot flat, rough, and unfinished. You must refine this “foot” in a process called “trimming.”

But, you can’t turn the pot over and trim the foot immediately. The clay is too soft. The entire thing will fold in on itself and collapse in a floppy mess.

You must wait until the clay dries and becomes more firm, what’s called “leather-hard.”

Leather-hard clay is at the perfect stage between wet and dry. It’s strong enough to hold itself up and withstand a bit of pressure but also soft enough to be workable, able to be cut and shaved and then smoothed and burnished.

This is where I got into trouble.

You see, depending on the conditions in the studio, clay can take between hours and days to dry. It has a rhythm to it. You can’t rush it. Like a peevish old man, it tells you go away and come back when it’s ready.

But I never had the patience. I was often too early. Or too late.

The results were predictable. If I attempted to trim before the pots were dry enough, they would twist and deform. Or if I missed the window and the clay dried too much, bits would break off and shatter and crumble. Even the survivors had feet that were rough and ugly.

Years later, I look at those feet and shake my head. My impatience — my insistence on going to the studio on Tuesday instead of Thursday because it fit my schedule better — had lasting consequences for my craft.

I wasn’t willing to work with the clay on its terms. I wanted it to work on mine. In the end, neither of us got what we wanted.

Properties and constraints

Every material has a personality.

In technical language, you’d say that different materials have different properties. These properties affect, among other things, how a material looks and feels, its ability to hold and transfer heat, its weight, how pliable or brittle it is under various types of strain.

A material’s properties shape the kinds of things you can and can’t do with the material. In designer language, you’d say that a material’s properties impose constraints.

Steel is very hard, but it’s also flexible. Thus, it’s an excellent material for building large structures.

Gold is much softer and heavier. It wouldn’t work well to support buildings. A gold megastructure would likely collapse under its own weight.

Yet gold is rarer and easier to work by hand than steel. For historical, economic, social, and aesthetic reasons, it’s more highly valued. Combine its workability and desirability and it makes a fantastic material for jewelry.

If you want to build a skyscraper, use steel. If you want to make a wedding ring, use gold.

Thus, a material’s properties inform its use:

- They affect the purposes to which you can put a material. (towers vs. rings)

- They affect the experience of the material. (dull grey and flat vs. reflective, yellow, intricately worked)

- They affect the process of working with the material. (forge vs. hand tools)

A material for the mind

So, what does all this have to do with storytelling?

Well, story itself is a material.

It has a personality. It has properties that make it well-suited for some uses and a poor fit for others. It has aesthetic qualities, a certain feel to it. It has constraints that place demands on your process.

The job of a good storyteller is to understand this personality and work with it.

This is what so much of craft advice is really about. When you hear people talk about story structure and the Hero’s Journey, or hooks and open loops, or red herrings and deus ex machina, what they’re talking about is the material. This is story’s grain.

But story is not a physical material. It is a material for communication, a material of the mind. The properties of story are based on how human brains perceive and process information. Stories succeed when they fit humans. Otherwise, they fail.

In the next few notes, we’ll unpack this more. We’ll look individually at how story’s nature as a material informs its purposes, experience, and process.

Are you ready? Let’s get some clay, center it on the wheel, and start making pots.

Who knows, by the end of this, if we’re very patient and present, we may even end up with some decent-looking feet.

Onward!

Rate this note

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.