Storytelling and the rule of three: trajectory and payoff

Summary: The rule of three is a powerful storytelling mechanic that leverages human psychology to set up and pay off audience expectation in a satisfying way.

“When you name several things you save the most impressive for last. ‘The Mayor,’ you say, ‘was there, and the Governor — and the President!’”

— Lajos Egri (Egri, Page 258)

The rule of three is a powerful and efficient, three-unit storytelling structural mechanic. It leverages human psychology to set up and pay off audience expectation. Where storytelling techniques like comparison and bracketing are about communicating meaning to your audience, you can use the rule of three to deliver lasting, memorable satisfaction.

You construct the rule of three by stringing together three things in such a way that audiences can tell they are similar or related. This creates a progression among the items. For example, in the words of webcomic author and Writing Excuses podcast co-host Howard Tayler, it’s, “beat, beat, punchline. Thing one, thing two, thing three, where we are escalating . . . We have three beats, and the third one is the longest, and the third one is the most specific.” (Kowal et al.)

The rule of three appears in many forms of storytelling. It is, perhaps, most obvious in folk tales, like the tale of The Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, or The Little Girl and the Swan Geese. (In the first two examples, “three” is even in the name.) But the rule of three isn’t limited to children’s stories. You can find it applied to all levels of story, from line-level prose and dialog to individual beats to scenes to whole sequences and acts. The existence of story trilogies speaks to the power of the form.

One reason for the ubiquity of the rule of three is its efficiency. Three is the minimum number of items needed to first establish a trajectory and then pay it off.

How it works: trajectory and payoff

Under the hood, the rule of three works by harnessing our human brains’ capacity recognize patterns and make predictions.

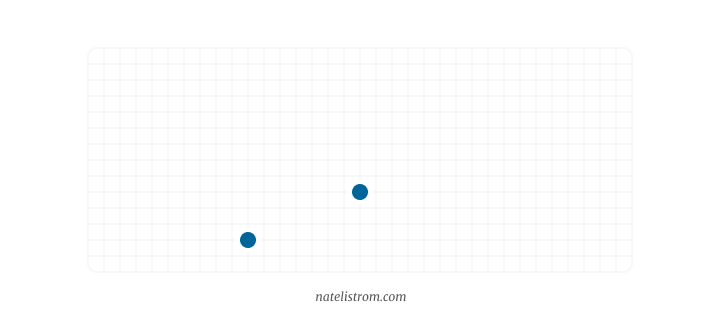

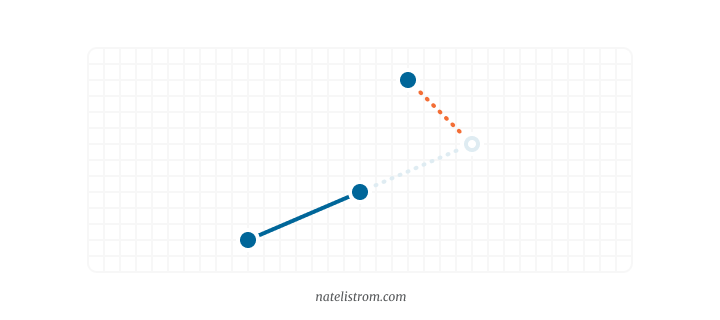

Imagine, for a moment, that you draw two dots on a sheet of paper.

An observer could look at those two dots and mentally draw a line connecting them. (In fact, because of the way our brains work, it’s likely that your brain will at least do this briefly.)

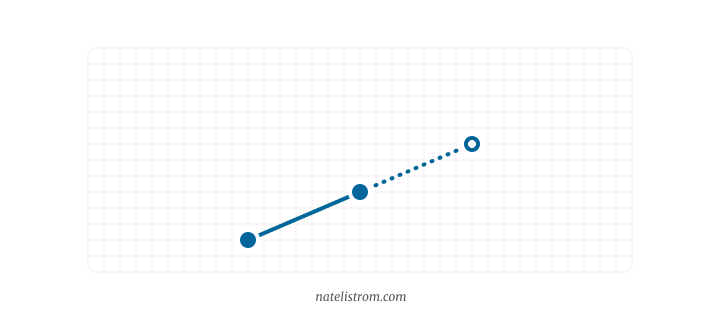

Seeing the mental line between the dots, an observer’s brain could extend the pattern and make a reasonable prediction about where a third dot might be drawn. In essence, you’ve created a trajectory.

We humans are especially good at making these kids of predictive inferences. It’s built into us. Author and story coach Lisa Cron puts it well: “We’re wired to predict what will happen next, and the way we do this is by charting patterns.” (Cron, Page 159) (Emphasis mine.) When we see what looks like a partial pattern, we almost can’t help but predict how the pattern will complete.

The rule of three leverages this human tendency toward pattern-based predictions, but rather than dots on a graph, it does this with story units.

- The hunter saw the stag. (beat one)

- He raised the rifle to his shoulder and aimed . . . (beat two)

The trajectory is set. The audience has an expectation. The hunter will pull the trigger. The gun will fire. The stag will die. (Or, the hunter will miss, and the stag will escape.)

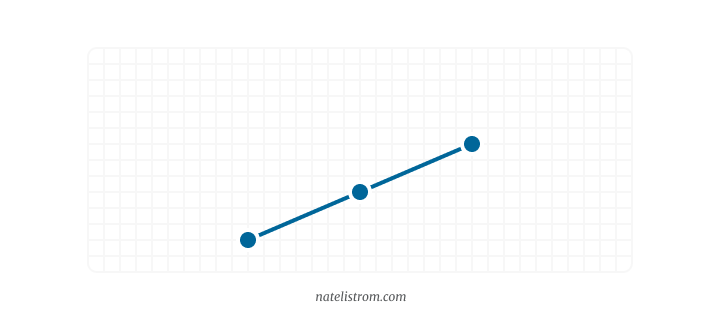

The first two units give a promise to the audience, creating expectation. For a satisfactory experience, that expectation must be paid off. That’s what the third unit does.

Payoff with a twist

It’s fine to pay off the trajectory in a way that fulfills the promise set up by the first two beats, but the most satisfying execution of the rule of three does something more.

What might that look like?

Take a look at this famous, “six word story” sometimes attributed to Hemingway:

“For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

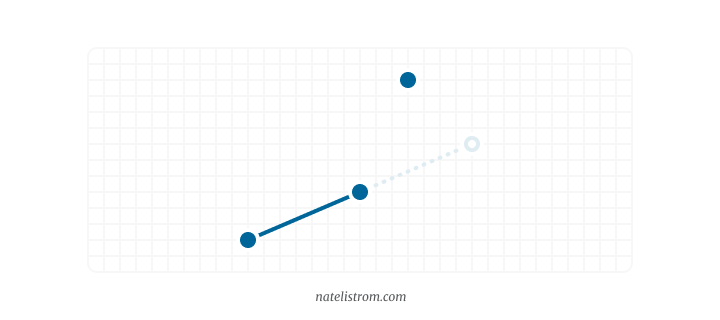

This masterfully uses the rule of three to set up a trajectory, but rather than delivering a promise that matches the direction set up by the first two units, the third unit goes somewhere else.

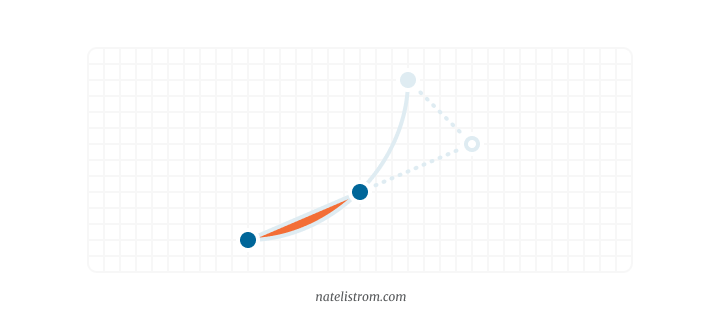

Now, all of a sudden, things get interesting. The trajectory established by the first two beats has been subverted. As an audience, we’re forced to focus in, to try to incorporate this new, unexpected information.

As we begin to process the outcome, our brains quickly evaluate the difference between what we predicted and what actually occurred. How different was the outcome? How far was it from what we predicted? Is the reality better than expected or worse?

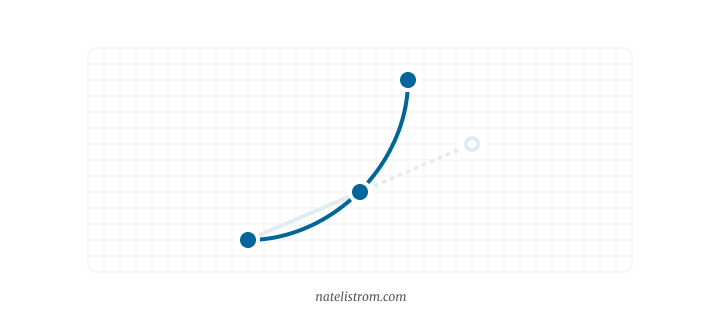

As we focus, our brains attempt to account for the difference and update our mental models of the world. They make new connections. Perhaps we realize that, instead of charting a straight line, the arc of the story was charting a curve all along.

This realization has a cascade effect. The new understanding not only shifts our view of the current story beat, it re-contextualizes what came before.

Our brains compare the difference between what we thought we knew and what we know now, and this creates new understanding.

Subjectively, we can experience this as a little flash of pleasure or insight — an “‘aha!’ moment.” If profound, the discovery can feel like an epiphany.

In the case of the “six word story,” most audiences feel a piquant sense of second-hand grief as their brains make the connection and internalize the perspective of expectant parents experiencing the loss of their child.

The most effective executions of the rule of three manage this twist well. They perfectly fulfill the promise set up by the first two story units, but they do it in a way that subverts the trajectory, adding something new and unexpected and, ultimately, more impactful and satisfying.

Variations on a theme

In his systematic classification of Russion folktales, Morphology of the Folk Tale, folklorist Vladimir Propp identifies three different variants of the rule of three:

“Repetition may appear as a uniform distribution (three tasks, three years’ service), as an accumulation (the third task is the most difficult, the third battle the worst), or may twice produce negative results before the third, successful outcome.” (Propp, Location 1555)

Journalist and author Christopher Booker, in his landmark work, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, adds a fourth variation. (Booker, Page 231) His taxonomy is as follows:

- simple (what Propp calls “uniform distribution”)

- progressive (what Propp calls “accumulation”)

- contrasting

- dialectical

Simple and progressive

Both simple and progressive have to deal with items that are more-or-less the same to one another. The main difference that Propp and Booker draw is that in the progressive form, sets of three build, their items increasing in strength or value (either positively or negatively). (Booker, Page 231)

But even in the simple form, the items are placed in sequence. That sequence creates an implicit hierarchy, even if the value of the items themselves is the same. Thus, both simple and progressive expressions of the rule of three are, pragmatically, pretty similar. They have to do with similar things in sequence.

In the story of The Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf, the straw, wood, and brick used by pigs to build their houses are a great example of the progressive form. The materials create a set, each of whose items progressively increase in strength.

Contrasting

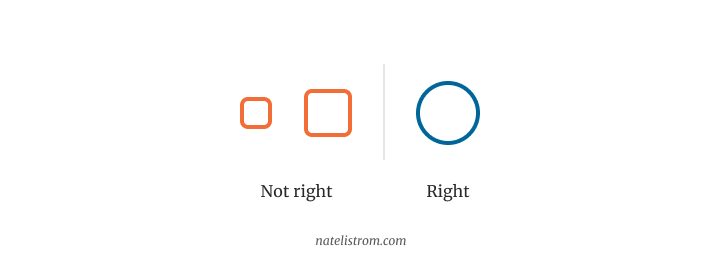

The contrasting three is a form where the first two items are negative or deficient in some way and stand in comparison to the third, which is positive and fulfilling. (Or, in tragedy, the first two are positive, but the protagonist rejects them and ends on a negative.)

This form also shows up in the story of The Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf. The first two houses, being built of weaker materials, are blown down by the wolf. The owners perish. The third house, built of stronger material, is the only one sturdy enough to withstand the wolf’s attack. It passes the test. The wolf goes away defeated, and the third pig lives.

Dialectical

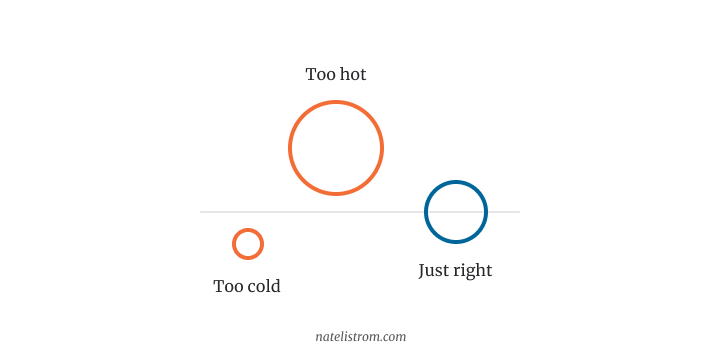

The last form, which Booker calls “dialectical,” is a form where the first and second items are in contrast to one another, but are alike in that neither one is acceptable. Only by bringing together elements of both in synthesis is a satisfying conclusion found in the third item. (Booker, Page 231)

As Booker points out, the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears plays with this form quite liberally, with its three bowls, three chairs, and three beds. In each triplet, the first two are unacceptable in divergent ways (the porridge too hot or too cold, the chairs too large or too soft, etc.) and the third is a happy medium; “just right.”

The forms build on one another

Drawn out like this, you can see that each of the three forms of the rule of three is built by layering complexity onto the previous form. The contrasting form takes the sequential element of the progressive form and adds a “right/not right” aspect. The dialectical form takes the “right/not right” aspect of the contrasting form and adds a synthesis element.

Beyond children’s stories

These forms are clear and — perhaps intentionally — obvious in nursery stories and fairy tales. But, their use isn’t limited to children’s stories. With a little bit of subtlety and sophistication, they can be used to great effect in stories for all audiences. They appear in many of the great classics.

For example, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol features a progressive rule of three in the ghosts of Christmas that appear to the protagonist.

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, there’s a powerful example of the contrasting rule of three in Elizabeth’s potential suitors. Collins is socially acceptable but a buffoon, someone who would be intellectual death for Elizabeth to marry. Wickham is attractive and winsome, intellectually interesting, but turns out to be scoundrel and morally repugnant. Only Darcy, whom Elizabeth rejects at first, turns out to (eventually) be everything she can admire and respect.

Because it’s more complex, the dialectical three is a bit harder to see. But it’s there. Many “fish out of water” stories feature a dialectical three where the protagonist must take elements of themselves from both their “ordinary world” and their “magical world” and merge them in a new way to finally undergo the transformation needed to overcome the challenge of the story. Joseph Campbell referred to this as the protagonist becoming “master of the two worlds.” (Campbell, Page 247)

Writer and director Craig Mazin sees this on the thematic level. He describes the dialectical three as the merging of thesis (what the protagonist believed at the story’s beginning) and antithesis (how the story proves that belief wrong) into synthesis (new, thematic knowledge expressed in the climax and resolution). (Mazin)

It seems that Booker would agree with that assessment.

“‘Three’ is the final trigger for something important to happen. Three in stories is the number of growth and transformation.” (Booker, Page 231)

Three makes for a good conflict

One last thing to say (today, at least) about the rule of three is that its capacity to establish a trajectory and then pay it off is especially useful when crafting a story’s opposition and conflict. Three is the minimum number of story units needed to make a conflict feel satisfying.

If a protagonist tries something one time and succeeds, there doesn’t seem much point in telling a story about it. It must not be very difficult.

If she tries and fails once and then, on the second attempt, succeeds, it likewise makes for a poor story. We grant that there was resistance, yes; but with only one failure and one success, we don’t yet know that the protagonist has learned anything or earned anything. Winning and losing could be pure coincidence.

But if the protagonist fails twice, we know for certain that failure is not random. A pattern has been established. The thing must be difficult.

Then, when she succeeds, it feels earned. We can cheer for her because we know she has struggled and fought in order to overcome.

“But then,” you may ask, “Why not more? What about four or five or six or seven? If two failures make success feel earned, won’t more failures make it feel even more earned?”

In one way, yes. And if your story has enough variation to support a longer series, that’s fine to pursue.

But it could backfire. Your audience has already gotten the basic pattern at two. Unless additional points of conflict vary the story in a meaningful way, they could feel like they’re wasting your audience’s time. What’s absolutely necessary is just the three.

Wrapping things up

There’s plenty more to say about the rule of three. It’s so basic and so broad in applicability that it shows up nearly everywhere. But it’s enough for now to say that it’s useful for story structure because it’s the most efficient way to set up a trajectory for your audience and then pay it off in a satisfying way.

Onward . . .

See also

- Writing Excuses 11.32: The Element of Humor (transcript)

- Nathan Baugh’s Worldbuilders essay on the rule of three (requires sign up; you can get the gist in this summary tweet.)

Change history

July 29, 2023: Added section on subversion of expectations and the “six word story.”

Rate this note

Read this next

Creating meaning with two consecutive story units

Human brains can't help but look for patterns, even when nothing's there. Storytellers can leverage this tendency, juxtaposing images in order to create rich and layered meaning.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.