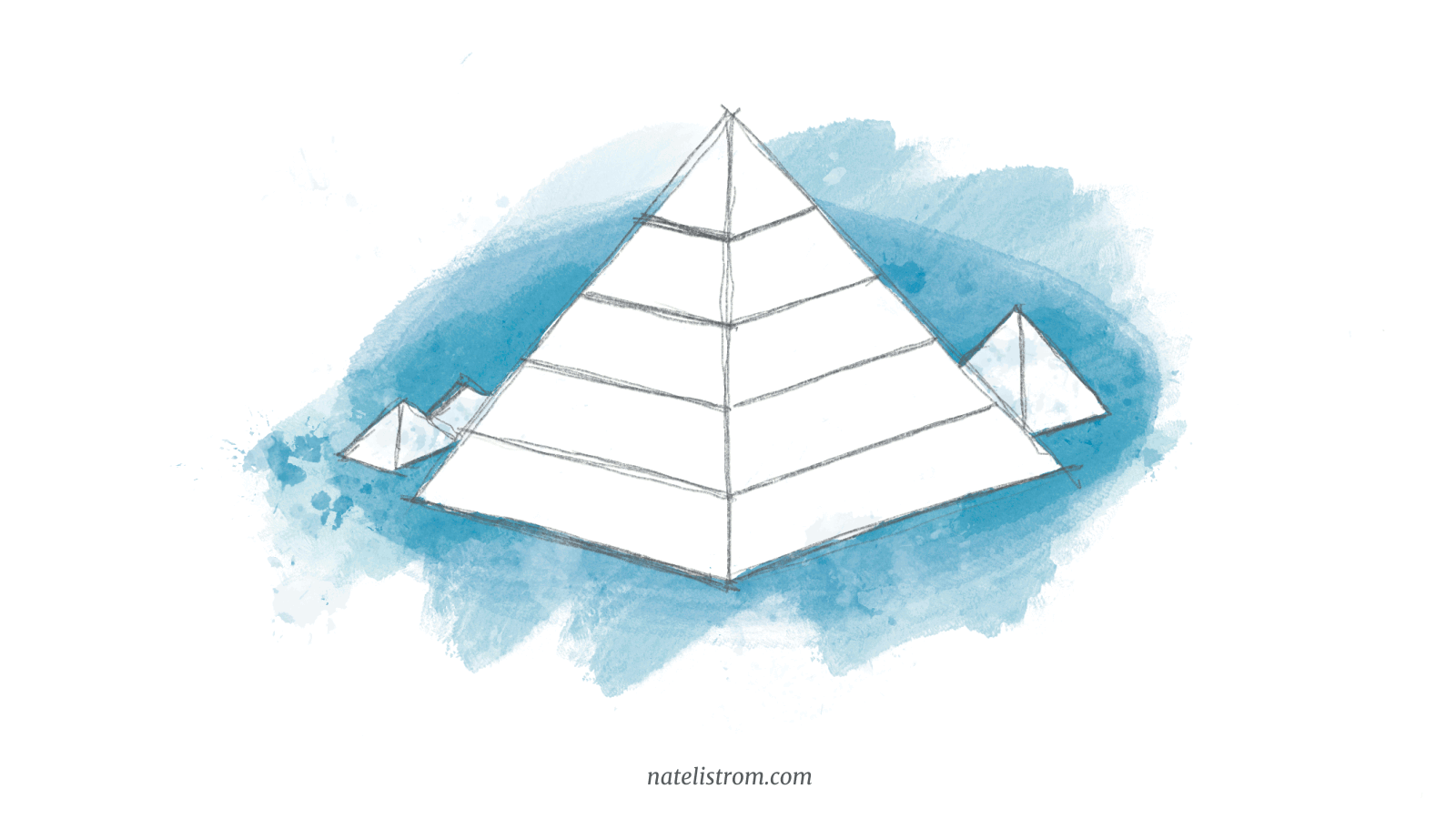

The story audience hierarchy of needs

The best stories — the ones that truly satisfy — fulfill five foundational requirements, which build on each other like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. These work because they fit the way human minds work.

Stories that satisfy are:

Nearly all the best storytelling advice can fit into one of these categories. Want to learn about story hooks? Look under “Engaging.” Want to know why story structure works? Find the answer under “Meaningful.”

On this page, I’ve arranged many of the best storytelling insights I’ve heard over the years into these five categories. I hope this will be useful to you on your storytelling journey.

And please note, dear reader, that this is a work in progress. There are rough edges. I am a human, so mistakes are possible.

Clear

Clarity is about understanding.

To write with clarity means that your audience gets what you’re trying to say. Or, if they don’t, they trust that you have made things intentionally confusing in order to give them a better payoff in the end. You owe it to them to make the pain of their confusion worthwhile.

Tips:

- Start with the basic grammar and spelling rules you learned in school. (Unless you have a compelling reason not to and your audience understands that you’re being intentional.) The rules aren’t there to hold you back. They ensure you and your audience are working from the same decoder.

- “Slaughter your darlings.” Remove unnecessary, distracting characters, plotlines, scenes, and prose.

- Flowery language isn’t bad in and of itself. But it is a problem when it pulls your audience out of the story. Then, it’s getting in the way of what you’re trying to say. Imagine trying to teach someone how to drive a car while constantly shoving a bouquet of roses in their face.

Notes for further reading:

Believable

Believability is about trust.

To write believably means that your audience has confidence in you. They may not agree with your decisions, but at least they don’t doubt your competence or your earnest intention. When your characters do things, your audience agrees that their behavior makes sense. Or, if it doesn’t make sense, your audience trusts that there is a reason, and that you will reveal it in a satisfying way at the right time.

Tips:

The key to believability is causality. Every event and character action should have a realistic motivation. Most of that time, the motivation should be visible to your audience in the moment.

- For events, the audience should be able to say, “I can see how that would logically happen, given what happened before.”

- For character actions, the audience should be able to say, “I can see why this person facing these circumstances would do that thing.”

- A sense of causality depends on preparing the ground ahead of time. Screenwriter Billy Wilder famously claimed, “If you have a problem with the third act, the real problem is in the first act.” The first place to look to fix a broken payoff is how you made the promise to begin with.

- The more wild and extraordinary the thing you’re asking your audience to believe, the more solid the preparation you’ll need. You can only cash out in the climax what you deposited earlier. Be sure you have sufficient funds.

- Know when to “show” and when to “tell.” Showing takes longer, but we believe it more. We don’t have to take your word for it; we can see it for ourselves. Your protagonist shouldn’t tell us she’s suffered — that’s complaining — let us experience a concrete moment when it happened.

Notes for further reading:

Engaging

Engagement is about attention.

To be engaging means that your audience wants to find out what happens. This relies on conflict, or — which I feel is a more useful term — “narrative drive.” I like to think of it as uncertainty that demands a resolution.

Tips:

- Create “open loops,” ask questions that your audience can’t get out of the backs of their minds, make irresistible promises of things to come.

- Prove you can deliver. Close your loops and answer your questions in satisfying ways. This will tickle your audience’s brains’ reward circuits, making them eager for more. It’s how hooks and zinger first lines work. Strong hooks demonstrate, right from the start, that you can make good on your promises. (The reverse can also happen. If your early payoffs fizzle, your audience can become skeptical of your ability and lose interest.)

- “Braid” your loops such that you open new loops before you close old ones. This keeps the momentum going.

- Create a character who has a goal and faces direct, overwhelming opposition to that goal.

- The more concrete the goal and the more tangible the opposition, the better. Your geeky, ninety-five pound mathlete protagonist doesn’t want love; he wants to pry the star cheerleader away from her chiseled, six-foot-ten quarterback boyfriend and take her to the prom. Let us know what success and failure look like.

- If your narrative drive is based on the goals of your protagonist, make sure that your audience cares about your protagonist. If we don’t care about the mathlete, we won’t care about his romantic ambitions either. Before you ask us to root for him to win the cheerleader, let us first watch him help his little sister with her homework and see how much she loves and admires her “brainy big brother.”

- One effective trick to create narrative drive that lasts for a whole story is to introduce some kind of story-spanning mystery, which the protagonist has a burning desire to solve. This is true for more than just mystery genres. The Harry Potter books illustrate this well.

- Human interest habituates quickly. This is one reason why you have to keep increasing the stakes. Once your audience has seen a level three obstacle, you can’t use it again. They’ll get bored unless the next obstacle is level four.

- The same effect applies to tension. This is why, paradoxically, you need to give your audience moments to rest. If the tension always increases at exactly the same rate in exactly the same direction, your audience will tire of it. A pop song that’s all chorus begins to grate after a while. Give us dynamics: verses, a vamp, a bridge, loud parts and quiet.

- Know what type of story you’re trying to tell and set your narrative drive based on that. There’s place in this world for both Dan Brown and Harper Lee.

Notes for further reading:

- How narrative drive works in the brain:

- Types of narrative drive:

Resources I recommend:

- “Brandon’s philosophy on plot — promises, progress, and payoff”, Brandon Sanderson

Brandon’s lectures on story craft are fantastic. (See what I did there?) His explanation of setup and payoff in this video is one of the best I’ve heard. - Techniques of the Selling Writer, Dwight Swain

Swain’s progression of “goal, conflict, disaster, reaction, dilemma, decision” has been foundational to my thinking on structure and narrative drive. - Save the Cat, Blake Snyder

One of the easiest craft books to pick up and read. It’s a great intro, though a bit overly prescriptive. The titular idea is a fantastic articulation of the need for (and one method of) getting your audience on your protagonist’s side.

Affecting

Affect is about feeling.

To be affecting means that your audience responds to your story with emotion, an experience of insight, laughter, fear, anger, cozy contentment, satisfaction.

Maya Angelou famously said, “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Storytelling is no different. People will forget if your story made sense or if they believed you or even if they were intensely interested. But they will never forget if your story made them truly, deeply feel.

Tips:

- In stories, you create emotional payoffs with the build and release of tension. The higher the rise and the steeper the dropoff, the more impactful.

- “It’s the reaction shot that sells the hit.” Watching characters grapple with the implications of events helps the audience feel them. Don’t skip past that too quickly.

- Relationships, especially family relationships, are a doorway to emotion. We want to see brothers caught on opposite sides of a civil war, a father striving for the sake of his son, a mother grappling with her daughter’s choice of lover.

- Generally, people feel most deeply when their core values are affirmed. We want to see heroic sacrifice recognized and perseverance in the face of overwhelming opposition rewarded. We want to see selfishness punished. Stories move us when they deliver these “just desserts.”

Notes for further reading:

- Sky lanterns and irony: How Disney’s ‘Tangled’ amplifies impact

- What makes a payoff affecting:

- How to build effective payoffs:

Resources I recommend:

- The Emotional Craft of Fiction, Donald Maass

Meaningful

Meaning is about significance.

At its most basic, meaning is about transferring concepts to your audience’s mind. This is a return to the idea of clarity — of creating understanding — but on a deeper level. While clarity is about removing obstacles to comprehension, meaning is about imbuing your story with substance.

To be meaningful means your story elevates your audience, gives them something that lasts beyond the edges of your story, affects their life in some enduring way. It doesn’t have to be world-changing . . . but in some tiny, perhaps almost imperceptible way, it does change the world.

The great classics, ancient and modern, work because they give people feelings and thoughts that combine in transformative ways.

Tips:

- On the most simple, mechanical level, you create meaning by juxtaposing one thing against another and letting your audience’s brains figure out how they’re related.

- A story theme is a rational argument that is proven experientially. Rather than making logical points that build the argument, you let your audience experience the truth through the events that happen to the protagonist and her responses.

- To build a thematic argument:

- Figure out what truth your protagonist must confront by the end of the story.

- In the beginning, have her believe the opposite: a lie.

- Illustrate the lie she believes through how she lives.

- Set up your story events to challenge her lie mercilessly.

- Have her defend her lie and hold onto it tenaciously.

- Persistently force her into a narrower and narrower corner until eventually she has only two unbearable options: let go of her lie (and much of her identity with it) or hold onto her lie, knowing that it isn’t true, and lose all hope for the future.

- Let her decide with path to take, and have her embody her choice through action in the climax.

- Have the story world reward or punish her in a way that underscores the theme.

- Make the elements of your story world resonate thematically. Your protagonist’s outward environment mirrors her inner journey.

- Working with a thematic argument can be like carpentry. You can start with an idea of what you want to build, but the wood has a grain. You need to work with the material, not against it. Some ideas won’t settle where you first try to put them, and some new things will emerge as you go.

Notes for further reading:

- Symbolism and irony in Mary Poppins

- Structure communicates meaning:

- Scenes and sequels help you structure your character arcs:

- Structural frameworks with which to experiment:

- The map and the mountain: Fifteen core beats of story structure

- Story structure and theme in Ira Glass’ anecdote and reflection

- Creating story arcs with three-unit brackets

- Storytelling with large-scale, complex bracketing structures

- Thesis, antithesis, and synthesis

- 7-part series on beginning, middle, and end

Resources I recommend:

- “How to Write a Movie”, Craig Mazin

One of the best explanations I’ve heard for how to build a thematic argument through Hegelian dialect. - “Screenwriting Plot Structure Masterclass”, Michael Hauge

A fantastic explanation of story structure on the level of popular movies. - Characters and Viewpoint (Chapter 5: What kind of story are you telling?), Orson Scott Card

Card’s MICE quotient is helpful for thinking about story structure.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.

Bonus 1: additional recommended reading

These are some of the resources I’ve found to be especially helpful, which aren’t listed above.

- A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, George Saunders

- Into the Woods, John Yorke

- The Art of Dramatic Writing, Lajos Egri

- Story, Robert McKee

- Story Grid, Shawn Coyne

Bonus 2: notes on craft and process

- Lazy engineers and hard-working tour guides

It’s the storyteller’s job to do the work. - Shinichi Suzuki and the three domains of mastery

Get in the reps! Practice is the one part of mastery that you control. - The spiral of refinement

Creative work takes iteration, always moving toward the center of perfection, never ultimately arriving there. - The skills to analyze and synthesize are different things

It takes different skills to create good stories vs. do good analysis of them. Both have their place. - The right 15%

Find your purpose, then pursue it.